--FIRST -PREV

"What have we learned, Palmer?"

"I don't know, sir."

"I don't &#!*@%$ know either. I guess we learned not to do it again."

-- Two CIA Officers from Burn After Reading

Fifteen decades later, what have we learned? Not nearly as much as the price on the box says it's worth, that's for damn sure.

The price ... the price was high. High enough to be nearly incomprehensible today. Even in purely monetary terms, it was staggering. Direct wartime costs amounted to $2.3 billion. Veterans' benefits -- benefits that, mind you, we were paying into the 1970s and 1980s to some wives and children -- amounted to $3.289 billion. Interest payments on the debt incurred during wartime came to $1.2 billion. The Federal debt at the end of the war stood at $2.7 billion, indicating that just about all wartime expenses were met by borrowing.

That's some serious cash. That's the Manhattan Project, Project Apollo, and just about everything in between, all rolled together. When you consider that the net worth of all slaves was in the neighborhood of $3.5 billion in 1860 dollars, it would have been cheaper -- far cheaper -- to buy out the slaveholders' interests. Cheaper, and far less bloody. Which brings us to the other kind of price.

Nearly three million Americans saw combat. Of those, over six hundred thousand died. About half that, three hundred thousand or so, were wounded. Right about a quarter of the South's men of military age were dead.

So ... what have we learned? I can hope that we have at a minimum learned not to do it again. But seeing all the Tea Partiers bleating "Secede!" at the least provocation, I despair of even that much.

But despair is a sin. The lessons are there, for those that care to look. I'm not going to pretend like I've got it all figured out -- I strongly suspect no one does -- but a few things have become clear to me over the last five years.

First, and this is no real surprise, the Lost Cause is utterly bankrupt intellectually. It hasn't the remotest basis in fact. Of the points listed in the article, the second is only tangentially true, and the fifth irrelevant. The others are hogwash, delusional fantasy, or outright lies.

(1) Southern commanders seemed better than their Union counterparts, but only because the South enjoyed the early advantage of putting their best officers in key posts.

(2) The Union's superiority in resources and manpower -- true, but this covers up the real reason.

(3) The loser's bleat -- we only lost because we were robbed. Buy a clue: Longstreet was right about Pickett's Charge, and Lee damned well ought to have listened.

(4) Horsefeathers. States' Rights to do what? The seceding States were perfectly clear why they seceded. This is an after-the-fact face-saving lie.

(5) Irrelevant. "Treason doth never prosper, what's the reason? For if it prospers, none dare call it treason." We say the American Revolution was justified, because we won. Secession failed, and therefore wasn't.

(6) I've actually never met anyone who could claim this with a straight face. We've made this much progress -- as recently as fifty years ago, a lot of people in the South took the hogwash that "slavery was a benign institution" more or less seriously.

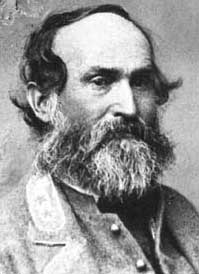

Be that as it may -- down here in the South, you will always and forever run into people that will say the Civil War wasn't about slavery. A small part of me sympathizes. It's a hard thing to admit that your great-to-the-Nth grandfather fought for an evil cause. No one likes to think that. Nonetheless, it's true. Well, individual soldiers fought for a whole bunch of reasons. In the end, he ends up fighting for the man on his right and his left, because that's the way you come through with a whole skin. But their officers, their leaders -- as I've said before, and repeatedly, they were crystal clear about why they did what they did. Secession was about slavery. To believe anything else is to ignore everything the secessionists themselves said or wrote.

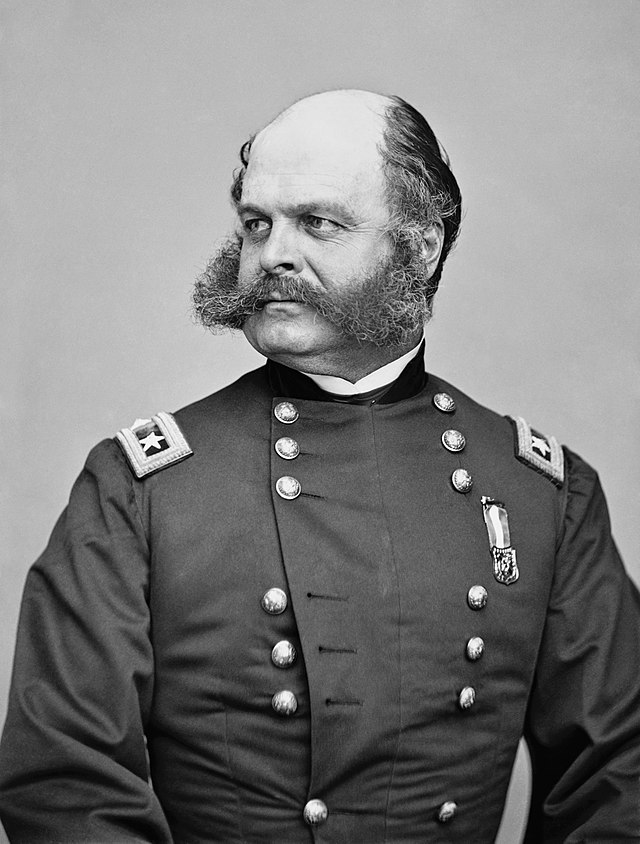

Second, this experience has reinforced a saying I learned many, many years ago during my days as an officer cadet: Amateurs study tactics, professionals study logistics. General Scott's overall strategy for the Union was shrink-wrapped around logistics: secure the Ohio River valley and its railroads, secure the Mississippi, isolate and starve the enemy. It set a pattern we still follow. It was more or less irrelevant whether or not the Tiger was ten times better than a Sherman, because there was always an eleventh and twelfth Sherman. We seek to ensure adequate arms and supplies for our own soldiers, and just as diligently seek to deny the same to our enemies. If you've got plenty of food, ammo, and gas and your enemy is scrounging; well, that may not be victory, but you can sure see it from here. Had they ever been able to get England off dead center, and use the Royal Navy to guarantee free navigation to Southern ports ... but that was never going to happen. It was a faint hope until late summer of 1863, but a dead one afterwards. In any event, the South wasn't crushed by numbers, or the perfidy of some of its officers, it was strangled by a slow, patient encirclement. Just as General Winfield Scott intended.

Third, and this came as something of a surprise, the battles themselves were far less interesting than I thought they'd be. After a while, they all began to run together. That said, you do see a difference between how the armies moved as the war progressed. Early on, they'd just run pell-mell at one another. Then, in late 1863 or early 1864, they began to emphasize flanking movements and de-emphasize frontal attacks. That was an interesting development. Officers began to realize the power of the weapons they commanded, and how they must be employed on the battlefield. And you begin to see in the siege of Petersburg in late 1864 and early 1865 a microcosm of what would happen on a continental scale only fifty years afterwards. Even then, though, the movements and decisions between the battles were, and are, what have a lasting effect. As Sun Tzu once said, a battle is won or lost before the armies ever see one another. It's purely a pity Master Sun's wisdom wasn't widely available in 1860.

Fourth, and last, it's not really over. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg, it is still up to us to carry on the work left undone. It is still up to us to see to it that the words "all men are created equal" have real weight and meaning, and isn't just an empty phrase. That "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" are things that each and every one of us can have and use. There are some who, upon realizing this, say that the war can still be lost.

I shun such defeatism. Rather, let us work to see to it that we truly experience a new birth of freedom. Six hundred thousand ghosts demand it. They expect us to take up the standard, worn and frayed though it be, and not rest until we've done our part such that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the Earth.

It's a worthy goal. And a life worthily spent. Truly, what more can a man want?

[Ed. note -- and that's a wrap. Thanks for taking this journey with me. In coming months, I'll be taking a spin through the articles, doing some light editing and fixing broken links.]

Showing posts with label CW Sesquicentennial. Show all posts

Showing posts with label CW Sesquicentennial. Show all posts

Sunday, May 10, 2015

Monday, May 04, 2015

Sesquicentennial, Part XLIX: Epilogue, Part 4: The Curious Case Of Dade County

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

"Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historical facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce." -- Karl Marx

And then there was the time, late in the War, that a county seceded from Georgia.

With respect to Georgia, Dade County defines remote. In the mid-19th century, swamps and forests make it impossible to reach Dade County by a road entirely within Georgia. You had to go through either Tennessee or Alabama to get there. And it's not like Dade County actually had anything worth having. For that matter, Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia had a bit of trouble remembering to whom Dade County actually belonged to begin with. The County government thought it belonged to Georgia, though, and when Georgia's demand for troops became too onerous, Dade County adopted an Ordinance of Secession, and bolted.

There's no record that the Georgia Legislature ever noticed. To be fair, they were preoccupied with more pressing matters, such as being where General Sherman wasn't. Time passed.

The war ended. The Confederate armies surrendered, and the soldiers went home. But Dade County either forgot -- or deliberately declined -- to re-unify with Georgia. Maps of Georgia would commonly have a notch in the corner, where Dade County ought to have been. Beyond that, no one really cared.

More time passed.

Men from Dade County volunteered to fight in the armies of the United States, first against Spain, and then against the Kaiser. A few oldsters thought that funny, since so far as any of them could remember, they weren't strictly speaking part of the United States.

Still more time passed.

Someone decided that it'd be nice to have a road to Dade County that lay entirely within Georgia. The discovery of coal deposits probably had something to do with the decision. They built it. The citizens of Dade County paid Georgia taxes. Just about everyone had forgotten the unpleasant secession business, and men from Dade County again volunteered to fight for the United States against Germany and Japan.

It was more or less at this point that a county historian discovered the old ordinance, in a disused file cabinet.

The government of Dade County, circa 1946, was astonished to learn that they were still, legally, in a state of rebellion against a government that now held a global monopoly on atomic weapons. This was an ... alarming realization, to say the least. But hey, late reunification is better than never, right? They promptly adopted an ordinance of reunion, with both Georgia and the United States, and sent it along to President Truman.

Truman was a good sport about it. All's well that ends well, as they say. And now that Dade County is safely and legally reunited with Georgia, the map of Georgia is once again whole, and properly pointy in all the right places. No one would ever again leave Dade County off.

"Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historical facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce." -- Karl Marx

And then there was the time, late in the War, that a county seceded from Georgia.

With respect to Georgia, Dade County defines remote. In the mid-19th century, swamps and forests make it impossible to reach Dade County by a road entirely within Georgia. You had to go through either Tennessee or Alabama to get there. And it's not like Dade County actually had anything worth having. For that matter, Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia had a bit of trouble remembering to whom Dade County actually belonged to begin with. The County government thought it belonged to Georgia, though, and when Georgia's demand for troops became too onerous, Dade County adopted an Ordinance of Secession, and bolted.

There's no record that the Georgia Legislature ever noticed. To be fair, they were preoccupied with more pressing matters, such as being where General Sherman wasn't. Time passed.

The war ended. The Confederate armies surrendered, and the soldiers went home. But Dade County either forgot -- or deliberately declined -- to re-unify with Georgia. Maps of Georgia would commonly have a notch in the corner, where Dade County ought to have been. Beyond that, no one really cared.

More time passed.

Men from Dade County volunteered to fight in the armies of the United States, first against Spain, and then against the Kaiser. A few oldsters thought that funny, since so far as any of them could remember, they weren't strictly speaking part of the United States.

Still more time passed.

Someone decided that it'd be nice to have a road to Dade County that lay entirely within Georgia. The discovery of coal deposits probably had something to do with the decision. They built it. The citizens of Dade County paid Georgia taxes. Just about everyone had forgotten the unpleasant secession business, and men from Dade County again volunteered to fight for the United States against Germany and Japan.

It was more or less at this point that a county historian discovered the old ordinance, in a disused file cabinet.

The government of Dade County, circa 1946, was astonished to learn that they were still, legally, in a state of rebellion against a government that now held a global monopoly on atomic weapons. This was an ... alarming realization, to say the least. But hey, late reunification is better than never, right? They promptly adopted an ordinance of reunion, with both Georgia and the United States, and sent it along to President Truman.

Truman was a good sport about it. All's well that ends well, as they say. And now that Dade County is safely and legally reunited with Georgia, the map of Georgia is once again whole, and properly pointy in all the right places. No one would ever again leave Dade County off.

Ummm ... guys?

Monday, April 27, 2015

Sesquicentennial, Part XLVIII: Epilogue, Part 3: ... And Dropping Them

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

"I yield to no one precedence in love for the South. But because I love the South, I rejoice in the failure of the Confederacy." -- Woodrow Wilson, March 1880

Is it possible to lose a war but win the peace?

Of course it is. You need look no further than Germany or Japan. If you had told one of the survivors, starving in blasted-out ruins in 1945, that in only a few short decades their nations would stand near the top of the entire world in economic growth, they'd have thought you insane. Looking back from 1970, though, it was fairly clear: Japan and Germany, far from being impoverished conquered provinces, were very wealthy and very free. They both lost their war, and by 1970 no one was all that heart-broken about it.

(As an aside, it's ironic that a liberalized and democratized Germany and Japan have achieved most of the goals that their totalitarian masters had set for influence and prosperity. But I digress.)

So it was with the South, more or less. They lost the war for independence, yes. But the patience of the Northern taxpayer would not last forever. And there were projects the Northern taxpayer had no real interest in undertaking.

The failures of Reconstruction, then, can be divided into two broad categories. First, the things the Congress never really tried to do; and second, the things it did, but stopped doing after a while.

The fundamental problem surrounding the abolition of slavery was this: aside from freedom, nothing had been given the freedman. He owned nothing, and had few to no skills. What was he supposed to do with himself? How would he earn a living?

There were half-hearted efforts by the Freedmen's Bureau to address this problem. Vocational training, for instance. And efforts to get them included in the Homestead Act. Get them a fair start with property and skills. Unfortunately the effort was starved and stymied from the start. The Freedmen's Bureau was basically gutted by 1869, and closed outright in 1872.

Even in its failure, though, there were successes. Schools and colleges were established all over the country, first simply to teach them to read and write, and then to address their needs for higher learning. And it was able to offer assistance and advice to freedmen who were adjusting to their new relationships, employee to employer rather than slave to master.

But this effort to address the fundamental issue -- that the freedman owned nothing and knew little -- was barely a drop in the bucket. And after 1872, Congress more or less forgot about the whole thing until the 1960s.

That leads us to the other reason for Reconstruction's failure: Northerners got tired of paying for, and staffing, a military occupation of the Southern states. You see, Lee was fundamentally right: the North would get tired of being on a war footing, sooner or later. It took ten to fifteen years to get there, though, far too long for the Confederacy to get any benefit.

In the immediate aftermath, the Republican super-majority in Congress could do what it damned well pleased. And often did, despite Jackson's veto. (Again, I think Lincoln would have handled this better ... but we'll never know.) The Radicals wanted, and got, a harsh version of Reconstruction that was essentially an army of occupation sitting on the South until ... well, until the North tired of the effort. While an army of occupation was sitting on top of them, they had to pay attention to things like the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. They had to pay attention to voting rights. That doesn't mean they liked it.

And so, to all intents and purposes, the minute the North looked away ... the South returned to a passable version of status quo ante. Black Codes were passed that were very little different from the Slave Codes they replaced. This system mutated a little over the years, to become the Jim Crow laws that basically ruled the South from the 1870s to the 1960s, 1970s, and in some places even later. The system that was in place by the turn of the century was very little different from that which had been in place forty years before.

There were a few differences, though. People were acknowledged to own themselves. And those who could get out, who could move North or West, found life a little more pleasant. Not a whole lot, because discrimination was rife in those places as well ... but once the soldiers left, the South re-imposed their preferred social order.

And so it was that by 1880 or thereabouts, a young Southerner could well celebrate the Confederacy's ruin. Well, not "celebrate" as such. But like Wilson, they could have both the advantages of being part of the Union, and enjoy the privileges of class that their fathers and grandfathers had known.

They had lost the war, but they had also won the peace.

"I yield to no one precedence in love for the South. But because I love the South, I rejoice in the failure of the Confederacy." -- Woodrow Wilson, March 1880

Is it possible to lose a war but win the peace?

Of course it is. You need look no further than Germany or Japan. If you had told one of the survivors, starving in blasted-out ruins in 1945, that in only a few short decades their nations would stand near the top of the entire world in economic growth, they'd have thought you insane. Looking back from 1970, though, it was fairly clear: Japan and Germany, far from being impoverished conquered provinces, were very wealthy and very free. They both lost their war, and by 1970 no one was all that heart-broken about it.

(As an aside, it's ironic that a liberalized and democratized Germany and Japan have achieved most of the goals that their totalitarian masters had set for influence and prosperity. But I digress.)

So it was with the South, more or less. They lost the war for independence, yes. But the patience of the Northern taxpayer would not last forever. And there were projects the Northern taxpayer had no real interest in undertaking.

The failures of Reconstruction, then, can be divided into two broad categories. First, the things the Congress never really tried to do; and second, the things it did, but stopped doing after a while.

The fundamental problem surrounding the abolition of slavery was this: aside from freedom, nothing had been given the freedman. He owned nothing, and had few to no skills. What was he supposed to do with himself? How would he earn a living?

There were half-hearted efforts by the Freedmen's Bureau to address this problem. Vocational training, for instance. And efforts to get them included in the Homestead Act. Get them a fair start with property and skills. Unfortunately the effort was starved and stymied from the start. The Freedmen's Bureau was basically gutted by 1869, and closed outright in 1872.

Even in its failure, though, there were successes. Schools and colleges were established all over the country, first simply to teach them to read and write, and then to address their needs for higher learning. And it was able to offer assistance and advice to freedmen who were adjusting to their new relationships, employee to employer rather than slave to master.

But this effort to address the fundamental issue -- that the freedman owned nothing and knew little -- was barely a drop in the bucket. And after 1872, Congress more or less forgot about the whole thing until the 1960s.

That leads us to the other reason for Reconstruction's failure: Northerners got tired of paying for, and staffing, a military occupation of the Southern states. You see, Lee was fundamentally right: the North would get tired of being on a war footing, sooner or later. It took ten to fifteen years to get there, though, far too long for the Confederacy to get any benefit.

In the immediate aftermath, the Republican super-majority in Congress could do what it damned well pleased. And often did, despite Jackson's veto. (Again, I think Lincoln would have handled this better ... but we'll never know.) The Radicals wanted, and got, a harsh version of Reconstruction that was essentially an army of occupation sitting on the South until ... well, until the North tired of the effort. While an army of occupation was sitting on top of them, they had to pay attention to things like the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. They had to pay attention to voting rights. That doesn't mean they liked it.

And so, to all intents and purposes, the minute the North looked away ... the South returned to a passable version of status quo ante. Black Codes were passed that were very little different from the Slave Codes they replaced. This system mutated a little over the years, to become the Jim Crow laws that basically ruled the South from the 1870s to the 1960s, 1970s, and in some places even later. The system that was in place by the turn of the century was very little different from that which had been in place forty years before.

There were a few differences, though. People were acknowledged to own themselves. And those who could get out, who could move North or West, found life a little more pleasant. Not a whole lot, because discrimination was rife in those places as well ... but once the soldiers left, the South re-imposed their preferred social order.

And so it was that by 1880 or thereabouts, a young Southerner could well celebrate the Confederacy's ruin. Well, not "celebrate" as such. But like Wilson, they could have both the advantages of being part of the Union, and enjoy the privileges of class that their fathers and grandfathers had known.

They had lost the war, but they had also won the peace.

Monday, April 20, 2015

Sesquicentennial, Part XLVII: Epilogue, Part 2: Picking Up The Pieces...

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

"Laws are to govern all alike -- those opposed as well as those who favor them." -- President Ulysses S. Grant, March 4, 1869

Reconstruction meant a lot of things.

Politically, it meant the re-integration of the Union. Physically, it literally meant the re-construction of cities, rail lines, and other infrastructure that had been blasted to rubble. It had many other meanings as well, so many that it's probably a hopeless task to cover it in one, two, or a hundred essays. The fact that it's still a matter of contention a century and a half later should tell you how complicated and convoluted a matter it is.

If it was a failure, it was also a limited success. I'd like to talk about the successes first.

The longest-lasting success was a fundamental alteration of the nature of the United States. Originally, the United States were envisioned as a compact amongst independent, sovereign States; banded together for the purpose of securing and protecting their independence first from Great Britain, and then from anyone else who might take an interest. And, by and large, this was how the United States of America thought of themselves, up until the 1860s.

That nation died in the conflagration that began at Fort Sumter and ended at Appomattox.

The United States that emerged from the Civil War thought of itself -- unquestioningly and unflinchingly -- as a single Union. One nation. Indivisible. You've probably said those three words fairly often, and may not have given much thought to what they meant. It's an expression of a new national identity, an identity Americans didn't actually have before. The Union veterans who returned home still felt an attachment to their home States, to be sure, but they'd stood shoulder-to-shoulder with their brothers-in-arms from other States, and had fought and bled for the same cause. The former Confederates who returned home could say the same. Like Shelby Foote once said, North and South alike, they no longer thought of the United States as an "are", they thought of it as an "is".

More to the point, though, the War established the supremacy of the Federal government over the States. It's pointless to elaborate. What was Appomattox, if not the ultimate expression of Federal supremacy? While you hear grumbling from time to time about States' Rights, and while we still have clear divisions of power amongst and between the various levels of government in this country, where the Federal tier asserts supremacy, they get it.

The next longest-lasting success were the three so-called Reconstruction Amendments to the United States Constitution.

Constitutional Amendments are important. The Constitution is the Law of the Land. What the Constitution permits is allowed everywhere, what it forbids is allowed nowhere. So when an Amendment adds a new thou shalt or thou shalt not, that's kind of a big deal. The Reconstruction Era added three new chapters to our fundamental law.

The Thirteenth Amendment was the only one President Lincoln lived to see. This was the amendment that banned slavery, everywhere in the United States and for all time. It was presented to the States for ratification on January 31, 1865. Lincoln didn't see it come into force, though; with its ratification by Georgia on December 8th, it was declared to have become law by Secretary of State William Seward on December 18th.

The Fourteenth Amendment proved to be far more important, though, and far more sweeping. The first section of the Fourteenth Amendment is probably the most-litigated section in the entire Constitution. Citizenship, due process, privileges and immunities, equal protection -- all of those come from the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment. It, along with the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteeing the right to vote regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude," were bitterly contested by the South. But both Amendments entered force anyway: the Fourteenth in 1868 and the Fifteenth in 1870. Whether or not the spirit of the law has always been observed is open to question .. but the law, once on the books, could be litigated by people demanding equal protection under the law.

Another of the successes of Reconstruction is less obvious. It's an old story. Revolution is followed by counter-revolution, coup, junta, in an endless cycle of recrimination and revenge. This was largely avoided after the Civil War. The soldiers were simply sent home, with none of them being tried for treason. Well, poor old Henry Wirz was hanged for commanding the Andersonville prison camp, held to account for the hell-hole it became. But besides him, not a single Confederate officer danced his last jig at the end of a rope. Lincoln didn't want to exact revenge, he wanted reconciliation. That is why he instructed Grant to offer Lee the terms he did, and Sherman offered similar terms to Johnson. The defeated rebels were simply allowed to pick up the pieces, and get on with their lives. Now, don't get me wrong, there was plenty of rancor in the hearts of ex-Confederates ... but with time, and generations, it does tend to fade. There's still ribbing between Northerner and Southerner, but it's verbal and not physical. We've managed to avoid the endless cycle of revenge that has riven so many countries over the years.

Of course, that masks some spectacular instances of post-War violence. But that's for next time, when we talk about Reconstruction's failures.

"Laws are to govern all alike -- those opposed as well as those who favor them." -- President Ulysses S. Grant, March 4, 1869

Reconstruction meant a lot of things.

Politically, it meant the re-integration of the Union. Physically, it literally meant the re-construction of cities, rail lines, and other infrastructure that had been blasted to rubble. It had many other meanings as well, so many that it's probably a hopeless task to cover it in one, two, or a hundred essays. The fact that it's still a matter of contention a century and a half later should tell you how complicated and convoluted a matter it is.

If it was a failure, it was also a limited success. I'd like to talk about the successes first.

The longest-lasting success was a fundamental alteration of the nature of the United States. Originally, the United States were envisioned as a compact amongst independent, sovereign States; banded together for the purpose of securing and protecting their independence first from Great Britain, and then from anyone else who might take an interest. And, by and large, this was how the United States of America thought of themselves, up until the 1860s.

That nation died in the conflagration that began at Fort Sumter and ended at Appomattox.

The United States that emerged from the Civil War thought of itself -- unquestioningly and unflinchingly -- as a single Union. One nation. Indivisible. You've probably said those three words fairly often, and may not have given much thought to what they meant. It's an expression of a new national identity, an identity Americans didn't actually have before. The Union veterans who returned home still felt an attachment to their home States, to be sure, but they'd stood shoulder-to-shoulder with their brothers-in-arms from other States, and had fought and bled for the same cause. The former Confederates who returned home could say the same. Like Shelby Foote once said, North and South alike, they no longer thought of the United States as an "are", they thought of it as an "is".

More to the point, though, the War established the supremacy of the Federal government over the States. It's pointless to elaborate. What was Appomattox, if not the ultimate expression of Federal supremacy? While you hear grumbling from time to time about States' Rights, and while we still have clear divisions of power amongst and between the various levels of government in this country, where the Federal tier asserts supremacy, they get it.

The next longest-lasting success were the three so-called Reconstruction Amendments to the United States Constitution.

Constitutional Amendments are important. The Constitution is the Law of the Land. What the Constitution permits is allowed everywhere, what it forbids is allowed nowhere. So when an Amendment adds a new thou shalt or thou shalt not, that's kind of a big deal. The Reconstruction Era added three new chapters to our fundamental law.

The Thirteenth Amendment was the only one President Lincoln lived to see. This was the amendment that banned slavery, everywhere in the United States and for all time. It was presented to the States for ratification on January 31, 1865. Lincoln didn't see it come into force, though; with its ratification by Georgia on December 8th, it was declared to have become law by Secretary of State William Seward on December 18th.

The Fourteenth Amendment proved to be far more important, though, and far more sweeping. The first section of the Fourteenth Amendment is probably the most-litigated section in the entire Constitution. Citizenship, due process, privileges and immunities, equal protection -- all of those come from the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment. It, along with the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteeing the right to vote regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude," were bitterly contested by the South. But both Amendments entered force anyway: the Fourteenth in 1868 and the Fifteenth in 1870. Whether or not the spirit of the law has always been observed is open to question .. but the law, once on the books, could be litigated by people demanding equal protection under the law.

Another of the successes of Reconstruction is less obvious. It's an old story. Revolution is followed by counter-revolution, coup, junta, in an endless cycle of recrimination and revenge. This was largely avoided after the Civil War. The soldiers were simply sent home, with none of them being tried for treason. Well, poor old Henry Wirz was hanged for commanding the Andersonville prison camp, held to account for the hell-hole it became. But besides him, not a single Confederate officer danced his last jig at the end of a rope. Lincoln didn't want to exact revenge, he wanted reconciliation. That is why he instructed Grant to offer Lee the terms he did, and Sherman offered similar terms to Johnson. The defeated rebels were simply allowed to pick up the pieces, and get on with their lives. Now, don't get me wrong, there was plenty of rancor in the hearts of ex-Confederates ... but with time, and generations, it does tend to fade. There's still ribbing between Northerner and Southerner, but it's verbal and not physical. We've managed to avoid the endless cycle of revenge that has riven so many countries over the years.

Of course, that masks some spectacular instances of post-War violence. But that's for next time, when we talk about Reconstruction's failures.

Sunday, April 12, 2015

Sesquicentennial, Part XLVI: Epilogue, Part 1 -- What If ...

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

"Buzzard's guts, man! I am the President of the United States, clothed in immense power! You will procure me those votes." -- President Abraham Lincoln (as portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis)

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford's Theater on April 15, 1865. And that's about all I have to say on that subject. A great deal has already been written about it, after all, and I don't think I have anything especially new or interesting to add to that conversation. Except ... for a curious observation.

Have you ever considered the fact that all of our Presidents who wielded sweeping wartime powers came to bad ends?

Abraham Lincoln basically invented the wartime Presidency. Invented it out of whole cloth, if we're being truly honest about it. Certainly there's no explicit definition of the powers Lincoln wielded within the Constitution. There's a splendid scene in the recent movie Lincoln, where Daniel Day-Lewis waxes eloquent on his powers, and their somewhat dubious Constitutionality. I'm paraphrasing a little, but he says in effect, "I took an oath to protect the Constitution, so I decided that in order to uphold that oath, I needed to have these powers." And, for the most part, no one called him on it. No one called him on it, so it became precedent. In World War I, and again in World War II, Presidents Wilson and Roosevelt, respectively, laid hold of those same powers.

And the record shows: Lincoln was assassinated, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke, and Roosevelt died scarcely a month before the victory in Europe.

It's almost enough to make you wonder if Someone didn't want them to last long enough to see peacetime...

And so we've never had the question answered: Can a President who's held so much untrammeled power come down the scale, and govern as a peacetime President?

It's probably just as well. The answer might have been "no." But let's assume the answer is "yes," at least in Lincoln's case, so we can move on to a very popular matter of speculation. To wit -- what would Lincoln's second term have actually looked like, were he not assassinated? Would Lincoln have fared better than Johnson?

The second question there is far easier to answer, so I'll answer it first with a confident and assured "yes." Lincoln was a damn sight better politician than Johnson, a better negotiator, and far more pragmatic. And more to the point, Lincoln, as the President who saved the Union, had an immense store of political capital upon which he could draw to get his way with Congress. The question that occupies us, and which brings us back to the first question above, is this -- on which issues would Lincoln spend that capital?

I have no real idea how to answer that question. I do know this, though; at least in its rough outlines, Presidential Reconstruction closely mirrored what Lincoln wanted. No harsh reprisals, and political re-integration into the Union as soon as practicable. He'd have run into Radical Republican opposition on this, just as Johnson did. But, Lincoln being Lincoln, he'd have done some horse-trading with them, giving them a little of what they wanted so he'd get most of what he wanted.

I think this is what Stephen Carter's book The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln gets a little bit wrong. I'm sure that Thaddeus Stevens would be angry enough at Lincoln to spit nails. But Lincoln is far too slippery, and far too pragmatic, to be caught so easily. Plus there's the aforementioned political capital, some of which he could spend defensively. He'd have a fractious relationship with the Radical wing of his party, but what else is new? Besides which, while the Republicans held a veto-proof majority in Congress, the Radicals didn't. Lincoln could play off the factions against one another long enough ... well, long enough. He only had to keep up the dance for four more years. Compared to the last four, it'd be a cake walk.

In this scenario, I think it's likely that Reconstruction wouldn't have been as extensive or as sweeping, but because Lincoln's reach didn't outrun his grasp, its effects may have lasted longer. I'm not sure exactly what form that would have taken. A better-funded Freedman's Bureau, perhaps, and/or a longer-lasting one. Smaller civil rights gains, but gains that actually bit and held, as opposed to being rapidly rolled back. Radicals chafed at Lincoln's "lack of vision", rather than seeing that Lincoln had little interest in that which could not be realistically achieved.

It would have been a contentious second term. Second terms almost always are. And Lincoln wouldn't have had any measurable appetite for a third one, so someone else takes over in 1868. Probably Grant, because he stood as high in everyone's esteem as anyone else did, and I don't see much of anything changing that.

But we'll never know. A disgruntled actor at Ford's Theater made sure of that. For good or ill, that's the world John Wilkes Booth left us. And so, we'll always wonder: What if...

"Buzzard's guts, man! I am the President of the United States, clothed in immense power! You will procure me those votes." -- President Abraham Lincoln (as portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis)

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford's Theater on April 15, 1865. And that's about all I have to say on that subject. A great deal has already been written about it, after all, and I don't think I have anything especially new or interesting to add to that conversation. Except ... for a curious observation.

Have you ever considered the fact that all of our Presidents who wielded sweeping wartime powers came to bad ends?

Abraham Lincoln basically invented the wartime Presidency. Invented it out of whole cloth, if we're being truly honest about it. Certainly there's no explicit definition of the powers Lincoln wielded within the Constitution. There's a splendid scene in the recent movie Lincoln, where Daniel Day-Lewis waxes eloquent on his powers, and their somewhat dubious Constitutionality. I'm paraphrasing a little, but he says in effect, "I took an oath to protect the Constitution, so I decided that in order to uphold that oath, I needed to have these powers." And, for the most part, no one called him on it. No one called him on it, so it became precedent. In World War I, and again in World War II, Presidents Wilson and Roosevelt, respectively, laid hold of those same powers.

And the record shows: Lincoln was assassinated, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke, and Roosevelt died scarcely a month before the victory in Europe.

It's almost enough to make you wonder if Someone didn't want them to last long enough to see peacetime...

And so we've never had the question answered: Can a President who's held so much untrammeled power come down the scale, and govern as a peacetime President?

It's probably just as well. The answer might have been "no." But let's assume the answer is "yes," at least in Lincoln's case, so we can move on to a very popular matter of speculation. To wit -- what would Lincoln's second term have actually looked like, were he not assassinated? Would Lincoln have fared better than Johnson?

The second question there is far easier to answer, so I'll answer it first with a confident and assured "yes." Lincoln was a damn sight better politician than Johnson, a better negotiator, and far more pragmatic. And more to the point, Lincoln, as the President who saved the Union, had an immense store of political capital upon which he could draw to get his way with Congress. The question that occupies us, and which brings us back to the first question above, is this -- on which issues would Lincoln spend that capital?

I have no real idea how to answer that question. I do know this, though; at least in its rough outlines, Presidential Reconstruction closely mirrored what Lincoln wanted. No harsh reprisals, and political re-integration into the Union as soon as practicable. He'd have run into Radical Republican opposition on this, just as Johnson did. But, Lincoln being Lincoln, he'd have done some horse-trading with them, giving them a little of what they wanted so he'd get most of what he wanted.

I think this is what Stephen Carter's book The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln gets a little bit wrong. I'm sure that Thaddeus Stevens would be angry enough at Lincoln to spit nails. But Lincoln is far too slippery, and far too pragmatic, to be caught so easily. Plus there's the aforementioned political capital, some of which he could spend defensively. He'd have a fractious relationship with the Radical wing of his party, but what else is new? Besides which, while the Republicans held a veto-proof majority in Congress, the Radicals didn't. Lincoln could play off the factions against one another long enough ... well, long enough. He only had to keep up the dance for four more years. Compared to the last four, it'd be a cake walk.

In this scenario, I think it's likely that Reconstruction wouldn't have been as extensive or as sweeping, but because Lincoln's reach didn't outrun his grasp, its effects may have lasted longer. I'm not sure exactly what form that would have taken. A better-funded Freedman's Bureau, perhaps, and/or a longer-lasting one. Smaller civil rights gains, but gains that actually bit and held, as opposed to being rapidly rolled back. Radicals chafed at Lincoln's "lack of vision", rather than seeing that Lincoln had little interest in that which could not be realistically achieved.

It would have been a contentious second term. Second terms almost always are. And Lincoln wouldn't have had any measurable appetite for a third one, so someone else takes over in 1868. Probably Grant, because he stood as high in everyone's esteem as anyone else did, and I don't see much of anything changing that.

But we'll never know. A disgruntled actor at Ford's Theater made sure of that. For good or ill, that's the world John Wilkes Booth left us. And so, we'll always wonder: What if...

Saturday, April 11, 2015

Sesquicentennial, Part XLV: The End, Part Two

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

"That was an order! Steiner's attack was an order! How dare you ignore my orders?!?"

-- Adolf Hitler, 4/22/1945

On April 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln sat at a desk. This wasn't especially unusual. He'd done so just about every day of his adult life, either as a student, attorney, Congressman or President. The fact he was sitting at a desk wasn't especially unusual, but the details -- at which desk, in particular -- were. Because this desk was in a particular city, at a particular place ... the city, Richmond ... the building, the Confederate White House.

Davis had departed in some haste a few days earlier, and the Confederate armies were in headlong retreat along the Appomattox River. Lincoln was sitting at the desk so recently occupied by his intractable adversary, contemplating what would come after. The war wasn't over yet, but it soon would be.

Green Eagle brought up a point that bears some examination. It's arguable whether or not history repeats itself, but there are definitely echoes, if you should care enough to listen for them. Jefferson Davis' call for eternal resistance has echoes eighty years hence, when Adolf Hitler bellowed incoherently at his senior generals in the bunker, raving about orders given to armies that no longer existed, except within his imagination. Of course, Hitler was taking up to nine injections per day of a witch's brew called Vitamultin, a frightening concoction devised by his "physician" Dr. Morell. Methamphetamine was but one of the ingredients. So, if you ever wondered why the Third Reich's overall strategy looked like the work of a hobo on crank ... yeah. Turns out, there's a reason for that.

Davis had no such excuse. Well, maybe he got hold of some moldy rye bread. I've heard that can make you see purple monkeys, among other things. Or maybe it was just stubborn pride. Pride's a hell of a drug. It can make a man do -- and say -- incredibly stupid things.

Lee was also a proud man, and stubborn, but not to that degree. He still had an army of sorts, and the means to resist. While his army was reeling from hammer-blow after hammer-blow during the retreat, the retreat never quite degenerated into a rout. There were supplies ahead, and ammunition. Maybe even a defensible position.

It's purely a shame that Phil Sheridan got there first.

And, at long last, that tore it. Lee was willing to resist as long as there were the means for doing so. But now? A good many of his men were unarmed. Those that were armed were desperately short of ammunition. No one had much food to speak of. Arms, ammunition, food; an army must have these to function as such. He now had none, and no hope of obtaining more.

It was more or less at this point that General Grant offered terms of surrender.

Once again, Grant here fails to live up to his nickname of "Unconditional Surrender", but this time it was at the behest of his Commander-in-Chief. Lincoln wanted him to offer generous terms. Officers could keep their sidearms. Officers and men who owned their horses could take them, too, and no one would examine that claim very closely. It was planting season, after all, and a surrendered population needs to be able to feed itself.

Lee said he'd rather die a thousand deaths than surrender ... but for the sake of his men, he accepted these terms, knowing he'd never get a better deal if he lived to be a hundred.

On April 9th, then, the Army of Northern Virginia stacked its arms and ceased to exist. Its men went home on parole.

Sporadic fighting would continue for months, here and there. But once word trickled through the South that Lee had given up ... Everyone was heartily sick and tired of fighting, of the privations of war. If Lee had surrendered, they they, too could surrender with their honor intact. But it would take time for the news to get around.

Joseph Johnston surrendered to Sherman later in the month of April. Other Confederate forces would surrender, in fits and starts as they got the news, all through the summer. The very last Confederate unit to surrender was the commerce raider CSS Shenandoah on November 6th. Importantly, Shenandoah surrendered to the Royal Navy rather than the US Navy, because her captain feared facing piracy charges.

Davis managed to evade capture for a while, but only for a while. Little more than a month after Lee's surrender, Davis was captured in Georgia.

What you called it depended upon whose side you were on. Some called it the Civil War. Others the War Between the States. But whatever you might have called it, it was over. Nearly three million Americans served, and over six hundred thousand died.

And now, the people who were left would have to clean up the mess.

[Ed. Note: There will be a few "Epilogue" chapters to come, dealing with Reconstruction and other things, so we're not quite done yet.]

"That was an order! Steiner's attack was an order! How dare you ignore my orders?!?"

-- Adolf Hitler, 4/22/1945

On April 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln sat at a desk. This wasn't especially unusual. He'd done so just about every day of his adult life, either as a student, attorney, Congressman or President. The fact he was sitting at a desk wasn't especially unusual, but the details -- at which desk, in particular -- were. Because this desk was in a particular city, at a particular place ... the city, Richmond ... the building, the Confederate White House.

Davis had departed in some haste a few days earlier, and the Confederate armies were in headlong retreat along the Appomattox River. Lincoln was sitting at the desk so recently occupied by his intractable adversary, contemplating what would come after. The war wasn't over yet, but it soon would be.

Green Eagle brought up a point that bears some examination. It's arguable whether or not history repeats itself, but there are definitely echoes, if you should care enough to listen for them. Jefferson Davis' call for eternal resistance has echoes eighty years hence, when Adolf Hitler bellowed incoherently at his senior generals in the bunker, raving about orders given to armies that no longer existed, except within his imagination. Of course, Hitler was taking up to nine injections per day of a witch's brew called Vitamultin, a frightening concoction devised by his "physician" Dr. Morell. Methamphetamine was but one of the ingredients. So, if you ever wondered why the Third Reich's overall strategy looked like the work of a hobo on crank ... yeah. Turns out, there's a reason for that.

Davis had no such excuse. Well, maybe he got hold of some moldy rye bread. I've heard that can make you see purple monkeys, among other things. Or maybe it was just stubborn pride. Pride's a hell of a drug. It can make a man do -- and say -- incredibly stupid things.

Lee was also a proud man, and stubborn, but not to that degree. He still had an army of sorts, and the means to resist. While his army was reeling from hammer-blow after hammer-blow during the retreat, the retreat never quite degenerated into a rout. There were supplies ahead, and ammunition. Maybe even a defensible position.

It's purely a shame that Phil Sheridan got there first.

And, at long last, that tore it. Lee was willing to resist as long as there were the means for doing so. But now? A good many of his men were unarmed. Those that were armed were desperately short of ammunition. No one had much food to speak of. Arms, ammunition, food; an army must have these to function as such. He now had none, and no hope of obtaining more.

It was more or less at this point that General Grant offered terms of surrender.

Once again, Grant here fails to live up to his nickname of "Unconditional Surrender", but this time it was at the behest of his Commander-in-Chief. Lincoln wanted him to offer generous terms. Officers could keep their sidearms. Officers and men who owned their horses could take them, too, and no one would examine that claim very closely. It was planting season, after all, and a surrendered population needs to be able to feed itself.

Lee said he'd rather die a thousand deaths than surrender ... but for the sake of his men, he accepted these terms, knowing he'd never get a better deal if he lived to be a hundred.

On April 9th, then, the Army of Northern Virginia stacked its arms and ceased to exist. Its men went home on parole.

Sporadic fighting would continue for months, here and there. But once word trickled through the South that Lee had given up ... Everyone was heartily sick and tired of fighting, of the privations of war. If Lee had surrendered, they they, too could surrender with their honor intact. But it would take time for the news to get around.

Joseph Johnston surrendered to Sherman later in the month of April. Other Confederate forces would surrender, in fits and starts as they got the news, all through the summer. The very last Confederate unit to surrender was the commerce raider CSS Shenandoah on November 6th. Importantly, Shenandoah surrendered to the Royal Navy rather than the US Navy, because her captain feared facing piracy charges.

Davis managed to evade capture for a while, but only for a while. Little more than a month after Lee's surrender, Davis was captured in Georgia.

What you called it depended upon whose side you were on. Some called it the Civil War. Others the War Between the States. But whatever you might have called it, it was over. Nearly three million Americans served, and over six hundred thousand died.

And now, the people who were left would have to clean up the mess.

[Ed. Note: There will be a few "Epilogue" chapters to come, dealing with Reconstruction and other things, so we're not quite done yet.]

Friday, February 13, 2015

Sesquicentennial, Part XLIII: Looking Ahead, Looking Back

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

One hundred years ago, the Western Front had settled down into an awful stalemate. A system of trenches stretched from the Swiss border to the North Sea, and the land in between the trenches had been turned into a churn of mud by the combined efforts of German, Austrian, French, and British artillery. The men in those trenches probably thought to themselves that surely, no such vision of Hell had been brought to Earth before.

Except that, if any of them had thought to cast their sight back fifty years in time and two thousand miles to the west, they'd see quite clearly that it had.

The Siege of Petersburg was, in many ways, a preview of coming attractions.

Trenches? Check. Massive artillery pounding the Hell out of everything in sight? Check. Crazy plans to dig mines under the enemy works and pack them with explosives? Good God yes, check. People had every right to feel despair, disgust, dread, or any number of other emotions regarding what the Western Front had become ... but they had no right at all to feel surprised. The Western Front was really nothing more than Petersburg scaled up to fit a continent.

Granted, the Western Front nightmare lasted a good bit longer. But that's partly because Douglas Haig wasn't fit to stand in the company of either Grant or Sherman.

True, Lee was keeping Grant's army out of both Petersburg and Richmond. He was also pinned down there, unable to do anything but hold those two cities. He was also unable to keep Grant from extending his lines around Petersburg to the south, and Richmond to the north.

That was eventually going to be a problem.

You see, there was more to Sherman's plan than simple bloody-minded violence. Part of that can be seen by a modification to a map of Confederate railroads (the original can be found here).

Sherman's approximate line of march since jumping off in Spring 1864 is shown in orange. By mid-February, Sherman had reached the city of Columbia in South Carolina. That encounter ... went poorly for Columbia. Sherman claimed that he didn't order Columbia burnt to the ground ... but he wasn't exactly sorry it happened, either. That's neither here nor there, though; the main point I want to make is that he was exacting the maximum amount of damage possible against the Confederacy's ability to move supplies from where they were to where they weren't. Where they were tended to be the farms where food was grown and the shops where goods were made, and where they weren't was the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee had exactly one life-line left open. And that was the rail line from Richmond to Danville. This had been recently connected to Greensboro in North Carolina, so in theory Lee could draw on supplies from points south ... except that due to Sherman's efforts, there wasn't much further south from which to draw.

This is more or less the point in a chess match at which you'd resign.

You resign in a chess match when you see the inevitable outcome, and know that no matter what move you make, even if you make the best move possible from your current position, you will lose. Your opponent will put your King in checkmate, and there's nothing you can do about it.

But Jefferson Davis was at least in nominal control, and he wasn't in a resigning mood. Was this stubborn pride, delusional lunacy, or some mix of the two? Because Davis had to have known the jig was well and truly up. Had to. He was a West Point man himself, and had enough military experience out on the sharp end to know what's what. But pride ... his pride would not allow him to admit he'd been beaten. Nor would it allow him to breathe a word of defeatism to another living soul.

No, surrender wasn't a word in Davis' vocabulary. So long as it was up to him, he'd grind it out to the last desperate inch.

And so it would go.

One hundred years ago, the Western Front had settled down into an awful stalemate. A system of trenches stretched from the Swiss border to the North Sea, and the land in between the trenches had been turned into a churn of mud by the combined efforts of German, Austrian, French, and British artillery. The men in those trenches probably thought to themselves that surely, no such vision of Hell had been brought to Earth before.

Except that, if any of them had thought to cast their sight back fifty years in time and two thousand miles to the west, they'd see quite clearly that it had.

The Siege of Petersburg was, in many ways, a preview of coming attractions.

Trenches? Check. Massive artillery pounding the Hell out of everything in sight? Check. Crazy plans to dig mines under the enemy works and pack them with explosives? Good God yes, check. People had every right to feel despair, disgust, dread, or any number of other emotions regarding what the Western Front had become ... but they had no right at all to feel surprised. The Western Front was really nothing more than Petersburg scaled up to fit a continent.

Granted, the Western Front nightmare lasted a good bit longer. But that's partly because Douglas Haig wasn't fit to stand in the company of either Grant or Sherman.

True, Lee was keeping Grant's army out of both Petersburg and Richmond. He was also pinned down there, unable to do anything but hold those two cities. He was also unable to keep Grant from extending his lines around Petersburg to the south, and Richmond to the north.

That was eventually going to be a problem.

You see, there was more to Sherman's plan than simple bloody-minded violence. Part of that can be seen by a modification to a map of Confederate railroads (the original can be found here).

Sherman's approximate line of march since jumping off in Spring 1864 is shown in orange. By mid-February, Sherman had reached the city of Columbia in South Carolina. That encounter ... went poorly for Columbia. Sherman claimed that he didn't order Columbia burnt to the ground ... but he wasn't exactly sorry it happened, either. That's neither here nor there, though; the main point I want to make is that he was exacting the maximum amount of damage possible against the Confederacy's ability to move supplies from where they were to where they weren't. Where they were tended to be the farms where food was grown and the shops where goods were made, and where they weren't was the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee had exactly one life-line left open. And that was the rail line from Richmond to Danville. This had been recently connected to Greensboro in North Carolina, so in theory Lee could draw on supplies from points south ... except that due to Sherman's efforts, there wasn't much further south from which to draw.

This is more or less the point in a chess match at which you'd resign.

You resign in a chess match when you see the inevitable outcome, and know that no matter what move you make, even if you make the best move possible from your current position, you will lose. Your opponent will put your King in checkmate, and there's nothing you can do about it.

But Jefferson Davis was at least in nominal control, and he wasn't in a resigning mood. Was this stubborn pride, delusional lunacy, or some mix of the two? Because Davis had to have known the jig was well and truly up. Had to. He was a West Point man himself, and had enough military experience out on the sharp end to know what's what. But pride ... his pride would not allow him to admit he'd been beaten. Nor would it allow him to breathe a word of defeatism to another living soul.

No, surrender wasn't a word in Davis' vocabulary. So long as it was up to him, he'd grind it out to the last desperate inch.

And so it would go.

Friday, January 02, 2015

Sesquicentennial, Part XLII: The Penultimate Campaign

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

"An army marches on its stomach." -- Napoleon Bonaparte

Atlanta had fallen, but John Bell Hood knew that wasn't necessarily the end. Sherman's men needed food, and supply. These, he'd have to get from the North. So, reasoned Hood, if he stood astride Sherman's line of supply, he'd have to come out and give battle on Hood's terms. It was with this general intent that Hood marched to the northwest, more or less leaving Georgia the way Sherman came in.

Sherman mounted a brief, half-hearted attempt to follow, then apparently gave it up as a bad idea. This perplexed Hood. He attacked Union forces at Spring Hill, then at Franklin, finally attacking Nashville itself in mid-December, but not a peep came from Sherman. Did Sherman care nothing for his lines of supply?

Hood, in the end, accomplished nothing but the destruction of the Army of Tennessee as an actual fighting force. I wonder if Hood knew what Sherman's plan actually was.

Because Sherman had deduced the dread secret of industrial-age war. Armies marched on their stomachs, yes. But that's a sword that cuts both ways. There are more ways than one to deny Lee's army of its supply. And there are more ways than one of supplying his own men at the same time. And Georgia's rich farmlands had not, as yet, felt the hard hand of war...

This was the bold plan he'd advanced to Grant and Lincoln, so bold that it bordered on suicidal rashness: cut loose. Head southeast towards Savannah, relying on the farmlands themselves for his sustenance. On the way, tear up telegraph wires, rail lines, and anything else of military significance. He had over sixty thousand men, even after cutting General Thomas and his men loose to keep Hood occupied in Tennessee. He had detailed maps drawn up, using data from the 1860 census, showing where the richest farms and plantations were, and what they'd be likely to have.

"I can make this march," Sherman wrote in a telegram to Grant, "And I will make Georgia howl!"

In opposition, General William Hardee could only muster some thirteen thousand troops with which to defend Georgia and the Carolinas. In open country ... that wouldn't be much of a fight. Hardee, not being an idiot, wasn't about to fight in open country. He fortified the approaches to Savannah as best he could, and awaited Sherman's arrival.

There were a few skirmishes along the way, but nothing really worth mentioning. The March itself remains somewhat controversial. His supporters have called Sherman the first modern general, the first to truly understand that by attacking the Confederacy's logistical underpinnings, he was taking the most direct path possible to defeating the Confederate armies in the field. His detractors call him many things -- some not repeatable in a family publication -- but also lay the charge of war criminal at his feet for making war upon civilians. He had an answer for them:

"You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have a peace and a division of our country. If the United States submits to a division now, it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal war. The United States does and must assert its authority, wherever it once had power; for if it relaxes one bit to pressure it is gone, and I believe that such is the national feeling."

Sherman believed that what he called "Hard War" (and what we would call today "Total War") made for a shorter conflict, and would lead to a swifter peace with less overall bloodshed. And to be sure, Sherman had drawn up orders to the effect that civilians were to be left unmolested, so long as they did not impede the army's march. Their excess produce would be confiscated, to be sure, but their persons were to be safe.

By mid-December, Sherman's army was arrayed outside of Savannah, and Sherman went about the business of reducing the fortifications that prevented his access to the sea -- and with it, communication with the Union Naval forces in command there. On December 17th, having made contact with Admiral John Dahlgren, he issued an ultimatum to General Hardee in Savannah. Surrender and accept generous terms, or resist and face obliteration. Hardee took a third option: he and his troops slipped out and escaped. In his stead, the mayor of Savannah surrendered the city to Sherman.

A few days later, Sherman telegraphed Lincoln:

"I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton."

Unwritten, but obviously implied and easily seen by anyone paying attention, was the fact that a Union army would roam at will through the Confederate heartland. That the Confederate army was powerless to defend the Confederacy. This is the point Lee had hoped to make with his two invasions of the North ... but didn't swing enough heavy iron to make the point stick.

Sherman had heavy iron to swing, and plenty to spare. The only question remaining was, who's next?

Actually, that's a trick question. Sherman was heading North, along the coast, to link up with Grant. South Carolina would be next to feel the sting. And there wasn't a blessed thing Jefferson Davis could do to stop him.

"An army marches on its stomach." -- Napoleon Bonaparte

Atlanta had fallen, but John Bell Hood knew that wasn't necessarily the end. Sherman's men needed food, and supply. These, he'd have to get from the North. So, reasoned Hood, if he stood astride Sherman's line of supply, he'd have to come out and give battle on Hood's terms. It was with this general intent that Hood marched to the northwest, more or less leaving Georgia the way Sherman came in.

Sherman mounted a brief, half-hearted attempt to follow, then apparently gave it up as a bad idea. This perplexed Hood. He attacked Union forces at Spring Hill, then at Franklin, finally attacking Nashville itself in mid-December, but not a peep came from Sherman. Did Sherman care nothing for his lines of supply?

Hood, in the end, accomplished nothing but the destruction of the Army of Tennessee as an actual fighting force. I wonder if Hood knew what Sherman's plan actually was.

Because Sherman had deduced the dread secret of industrial-age war. Armies marched on their stomachs, yes. But that's a sword that cuts both ways. There are more ways than one to deny Lee's army of its supply. And there are more ways than one of supplying his own men at the same time. And Georgia's rich farmlands had not, as yet, felt the hard hand of war...

This was the bold plan he'd advanced to Grant and Lincoln, so bold that it bordered on suicidal rashness: cut loose. Head southeast towards Savannah, relying on the farmlands themselves for his sustenance. On the way, tear up telegraph wires, rail lines, and anything else of military significance. He had over sixty thousand men, even after cutting General Thomas and his men loose to keep Hood occupied in Tennessee. He had detailed maps drawn up, using data from the 1860 census, showing where the richest farms and plantations were, and what they'd be likely to have.

"I can make this march," Sherman wrote in a telegram to Grant, "And I will make Georgia howl!"

In opposition, General William Hardee could only muster some thirteen thousand troops with which to defend Georgia and the Carolinas. In open country ... that wouldn't be much of a fight. Hardee, not being an idiot, wasn't about to fight in open country. He fortified the approaches to Savannah as best he could, and awaited Sherman's arrival.

There were a few skirmishes along the way, but nothing really worth mentioning. The March itself remains somewhat controversial. His supporters have called Sherman the first modern general, the first to truly understand that by attacking the Confederacy's logistical underpinnings, he was taking the most direct path possible to defeating the Confederate armies in the field. His detractors call him many things -- some not repeatable in a family publication -- but also lay the charge of war criminal at his feet for making war upon civilians. He had an answer for them:

"You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have a peace and a division of our country. If the United States submits to a division now, it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal war. The United States does and must assert its authority, wherever it once had power; for if it relaxes one bit to pressure it is gone, and I believe that such is the national feeling."

Sherman believed that what he called "Hard War" (and what we would call today "Total War") made for a shorter conflict, and would lead to a swifter peace with less overall bloodshed. And to be sure, Sherman had drawn up orders to the effect that civilians were to be left unmolested, so long as they did not impede the army's march. Their excess produce would be confiscated, to be sure, but their persons were to be safe.

By mid-December, Sherman's army was arrayed outside of Savannah, and Sherman went about the business of reducing the fortifications that prevented his access to the sea -- and with it, communication with the Union Naval forces in command there. On December 17th, having made contact with Admiral John Dahlgren, he issued an ultimatum to General Hardee in Savannah. Surrender and accept generous terms, or resist and face obliteration. Hardee took a third option: he and his troops slipped out and escaped. In his stead, the mayor of Savannah surrendered the city to Sherman.

A few days later, Sherman telegraphed Lincoln:

"I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton."

Unwritten, but obviously implied and easily seen by anyone paying attention, was the fact that a Union army would roam at will through the Confederate heartland. That the Confederate army was powerless to defend the Confederacy. This is the point Lee had hoped to make with his two invasions of the North ... but didn't swing enough heavy iron to make the point stick.

Sherman had heavy iron to swing, and plenty to spare. The only question remaining was, who's next?

Actually, that's a trick question. Sherman was heading North, along the coast, to link up with Grant. South Carolina would be next to feel the sting. And there wasn't a blessed thing Jefferson Davis could do to stop him.

Friday, November 07, 2014

Sesquicentennial, Part XLI: Decision '64, Part 2

--FIRST -PREV NEXT-

As late in the year as July, President Lincoln's re-election chances were looking sketchy, at best. The Republican Party was undergoing a split, similar to the one the Democrats suffered in 1860. The war had dragged on far longer than anyone had ever thought possible. One group of voters just wanted the war over, at any cost. The other wanted it won, by any means necessary. Neither group was happy with Mr. Lincoln.

But events conspired to deliver Lincoln a reprieve. One, we've already talked about: Sherman's capture of Atlanta. The other wasn't nearly as dramatic, but still important. A Union army under General Philip Sheridan had routed the Confederate army defending the Shenandoah Valley, and Sheridan had rendered the once-productive farmlands to a state such that it was said that a bird flying overhead would have to bring along its own rations. As is so often true, victory covers a multitude of sins. The Radical Republicans were somewhat mollified by the improved fortunes -- and the vindication of Lincoln's overall war plans those improved fortunes indicated. Fremont did get something for his trouble, though; as his price to drop his candidacy, he did manage to get the Postmaster General replaced.

History does not record what beef Fremont had with the existing Postmaster General, who was presumably doing an acceptable job.

Incidentally, there was no Confederate Presidential election. The Confederate Presidency was limited to a single six-year term, with the first actual election scheduled for 1866. Provided, of course, that the Confederacy would last so long.

The November election, when it came, was something of an anticlimax. The popular vote was much closer than the Electoral vote. Although the popular vote counts weren't what you'd call close -- Lincoln won 55% of the vote to McClellan's 45%. In the Electoral College the totals were much more lopsided, 212 to 21. McClellan won his home state of New Jersey, Delaware, and Kentucky. That was about it. Many Northern voters were tired of the war -- McClellan did quite well, winning a sprinkling of counties across the country -- but not enough of them were ready to throw in the towel just yet. With the events of the last year, particularly the last few months, they could smell a sea change.

And ... so could Southerners.

I think they knew they were doomed. Depending on who you ask they'll draw the line here or there, the point at which they knew the jig was up. Some will say Gettysburg, others Vicksburg. General D.H. Hill said Chickamauga was the breaking point ... ironically, a Confederate victory, but one they were unable to exploit. "It seems to me the élan of the Southern soldier was never seen after Chickamauga," Hill would later write. "He would fight stoutly to the last, but after Chickamauga, with the sullenness of despair and without the enthusiasm of hope." But I think it was the re-election of Lincoln that well and truly drew a line under it. They first pinned their hopes on a foreign intervention that never came, and then upon a Northern war-weariness and exhaustion that would not come in time. Undergirding it all was a reliance upon the daring and dash of their soldiers, and now that was gone, too.

But fight they would, with as much as they had, and with all the time they had left.

And so the war rolled on. The Southern armies still in the field had to be subdued. General Sherman in Atlanta had advanced a ... somewhat unconventional proposal to Grant and Lincoln. And, for all its risk and all his worries about it, Lincoln finally decided to let Sherman off the chain.

It was time to end this.

As late in the year as July, President Lincoln's re-election chances were looking sketchy, at best. The Republican Party was undergoing a split, similar to the one the Democrats suffered in 1860. The war had dragged on far longer than anyone had ever thought possible. One group of voters just wanted the war over, at any cost. The other wanted it won, by any means necessary. Neither group was happy with Mr. Lincoln.

But events conspired to deliver Lincoln a reprieve. One, we've already talked about: Sherman's capture of Atlanta. The other wasn't nearly as dramatic, but still important. A Union army under General Philip Sheridan had routed the Confederate army defending the Shenandoah Valley, and Sheridan had rendered the once-productive farmlands to a state such that it was said that a bird flying overhead would have to bring along its own rations. As is so often true, victory covers a multitude of sins. The Radical Republicans were somewhat mollified by the improved fortunes -- and the vindication of Lincoln's overall war plans those improved fortunes indicated. Fremont did get something for his trouble, though; as his price to drop his candidacy, he did manage to get the Postmaster General replaced.

History does not record what beef Fremont had with the existing Postmaster General, who was presumably doing an acceptable job.

Incidentally, there was no Confederate Presidential election. The Confederate Presidency was limited to a single six-year term, with the first actual election scheduled for 1866. Provided, of course, that the Confederacy would last so long.